Warners has two divisions releasing DVDs and Blu-Rays, and sometimes it’s like a Maverick gamble trying to figure out which release is coming from which section.

Maverick, Season 2 on DVD has apparently a broader appeal than, say, Cheyenne, which is another Warners Western series from the 1950s into the ’60s. Cheyenne is released through their Warner Archives; Maverick through Warner Bros. Home Entertainment Group. I think I have that right. I screwed it up once in writing to them, so we’ll see.

Both shows are from their library of TV series that brought Warner Bros. into the television arena. Shows like Maverick and 77 Sunset Strip were major league hits for the third network, ABC, at the time, and those shows, along with Walt Disney, helped make them a contender against NBC and CBS.

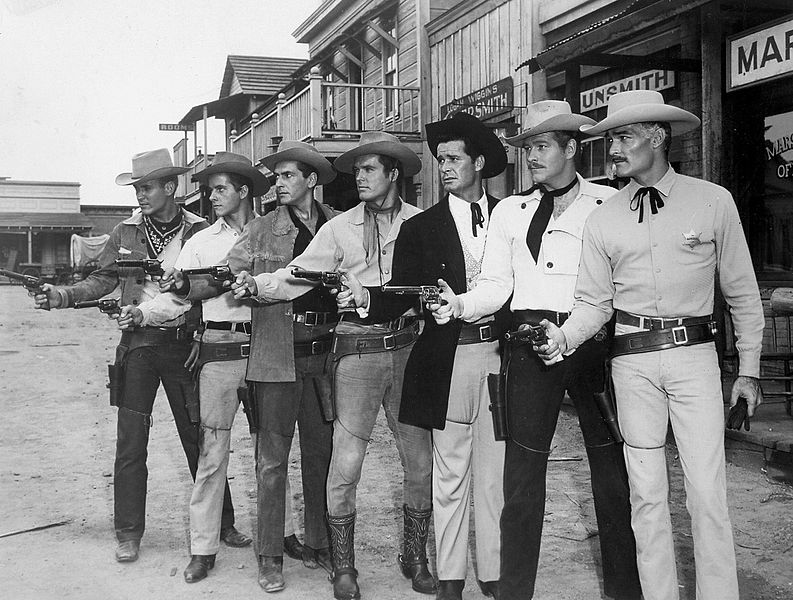

Season 2 of Maverick is the series at the top of their game. The distinctive tone of Maverick is more clearly defined than in Season 1. If Cheyenne played by Clint Walker is the iconic, soft-voiced, Gary Cooper film persona of the cowboy of integrity and loyalty, the Maverick brothers are essentially Cheyenne’s opposite; they are gamblers, their only real religion is the luck of the draw or outmaneuvering those that would cheat them. There are no better examples of this than in this newest set, packaged nicely, with good cover art of Bret and Bart with cards and chips in their hands.

Maverick, Season 2 has all 26 episodes, the story telling uncut, selling at a reasonable price.

(Side question: How did they get away with 26 episodes when most TV series at the time were producing a staggering number 39. 2nd side question: If they were going to do 39, how’d they come up with that number, why not an even 40?)

The images are sharp and clear for the most part, a few episodes have some night-time shots that have a faded gray look for a few minutes, but I note it without any negative reservations about recommending buying these collections.

This is the best Maverick has ever been seen of its best season. With the few minor exceptions, the picture quality is crisp and vital. The sound quality is excellent.

I’ve written about this before, but Warners still does not include any of the bumpers or trailers for their ’50s series, and especially with their private eye shows, but also their Westerns, they did these breaks better than anybody, with the possible exception of Disney. The breaks would come up with the theme-song playing, the announcer’s voice telling you the show would be back, and when it did, often with the title of that episode, as if, truly, you were seeing something special.

CBS certainly didn’t cut the tidal wave crashing toward shore in their Hawaii Five–O DVDs, or at the breaks, either. They kept the trailers for most episodes and gave the option of playing the trailers separately, or with the specific episode.

I’m not sure why they go through the bother of cutting the bumpers for their shows, unless it is because they have already done so in making prints for syndication. And I certainly would champion the option of watching the previews separately since sometimes they showed so much that those whose blood pressure rises at any kind of “SPOILERS!” would fall over in a dead faint, and have people dialing 911 for the emergency wagon. That written, I still believe, that the people who truly love these shows, the real collectors, want the DVD releases as close to the way they were originally broadcast as possible. I find it difficult to believe that many consumers would be bothered by the breaks; they know they are watching a TV show, they know there were commercials, and the bumpers just keep it together without having to sit through the ads for cigarettes and soup bowls filled with marbles under the vegetables.

I bring this subject back up because Warners is wisely expanding its series releases. Sugarfoot, with Will Hutchins, is surprisingly on the horizon. The Warner Bros private eye series, 77 Sunset Strip, Bourbon Street Beat, Hawaiian Eye and Surfside 6 are still hidden in the noir shadows of coming onto physical discs. Most people who track what is happening with what is now labeled “classic TV” feel that is it music rights that keep Stuart Bailey and Cricket Blake from being in a box they can hold in their hands and play whenever they like.

When Warners came into TV, it had a tremendous history of film, and a number of musicals in that history. The private eye shows made use of many standards. I never suspected Warners had any trouble with these songs as they used so many of them when they came to TV, but apparently there was no clause in the contract, because no one would suspect back then, that you could collect an entire season of a TV series and sell it to something called “fans.”

Third side question: In watching the entire set of Maverick, Season 2, I realized that they went back and forth between using the sung version of the theme song, “Who was the tall, dark stranger there, Maverick is his name,” to the instrumental version from the first season. Anyone know why Warners didn’t stick with the sung version? I’m almost certain that when they went into syndication they most always used to vocals. But I could be wrong.

Warners has wisely started its own streaming program, and they include 77 and Hawaiian Eye in there, because Connie Stevens can sing in every episode and bring something to even the worst episode of the series. I hope Warners can resolve their problems with music clearances because to be honest, for me, these are the series I would love to have, complete, uncut, restored. Missing episodes like 77‘s “Reserved for Mr. Bailey,” which I’ve written about before, might finally reach an audience again.

There is much written about streaming vs. the physical disc, the DVD or the Blu-Ray, until something replaces them. I believe the people who really love this stuff want to be able to hold that disc in their hands, or see the box with title and design within reach. I don’t think that will change the minds of those who like the idea of streaming, catching an episode when they can. The downside of streaming, at this point, is that if the particular company, Netflix or whoever, doesn’t continually renew its contract with the various companies, they will lose those shows, and then the viewer doesn’t have that option anymore of seeing the show whenever they want. Or the streaming company may not make a go of it, and what you had, you don’t anymore.

DVDs may corrode, for all I know. Video tape was supposed to disintegrate or some other damn thing, but I can tell you I can still play any tape I made during the 1980s.

The bottom line of this, in my plea to Warners, before you do release these shows in box sets, replace the bumpers and trailers, and the intros to Warners as being in the entertainment capital of the world!

Now, here is a plea to all of you reading this, and to Warner’s streaming service if they see this. I’m on AOL. Warners has invited me to their streaming service. However, I can’t get to it. Anytime I try a sign comes up telling me things are “incompatible” and no matter what I do, I can’t seem to get in to this secret club with these TV shows not available anywhere else.

Can anybody help me with this?

Please.

Now before anyone slaughters me as a maverick going away from Maverick for so long, which might be in keeping with the ad-line I used for selling Sabre in the late 1970s, it’s time to write about why the second season of Maverick is special to that series.

Jack Warner may have hated television when it first appeared; he may have reluctantly conceded to do shows for the medium. He may have had restrictive budgets, but he also had William T. Orr and Roy Huggins and Marion Hargrove and Douglas Heyes and Montgomery Pittman. What they had a keen eye for was talent.

In the second season of Maverick, James Garner’s charismatic charm, his wistful reluctance to violence, his disarming nature while outsmarting the chiselers and charlatans comes into full force. You can see Garner perfect that persona and never do it better than in episodes like “The Jail At Junction Flats,” acting with Efrem Zimbalist, Jr. as Dandy Jim Buckley, and atypical of any Western drama, ending with Garner hog-tied and losing to his antagonist in the last shot of the episode.

Then there is “Shady Deal At Sunny Acres”.

For most Maverick fans, this is one of their favorites in the entire run of the series. Ed Robertson in his book, Maverick: Legend Of The West, from Pomegranate Press, records that Roy Huggins offered Garner either role of the Maverick brothers, the one sitting in the chair, passively rocking, while telling an entire town that he is going to get the money back their banker (played delightfully by John Dehner) stole from him. Or he could play the other Maverick out to con Dehner and get his money back. Garner chose the rocking chair, whittling away at a piece of wood, telling anyone who asks how he is going to get the money he was swindled out of back.

“I’m working on it.”

Garner carries it with ease and exquisite timing.

“I’m working on it.”

Through-out the entire episode, just rocking and whittling and smiling.

I never realized until watching this set how much continuity there was on Maverick. Except for Desilu, there was not much continuity in TV series during that time. But Maverick has a number of people who come back from Dandy Jim Buckley to Samantha Crawford (Diane Brewster), Big Mike McComb (Leo Gordon), Gentleman Jack Darby (Richard Long, who would become Rex Randolph on Bourbon Street Beat), and Cindy Lou Brown (Arlene Howell). It always seemed to me that in most Warner TV series only Montgomery Pittman was allowed to get away with bringing characters back, and wondered why.

One of the other things you might discover watching this set is that Jack Kelly delivers solid performances as Brother Bart. He just isn’t James Garner. And he shouldn’t be. He’s Bret’s brother, not Bret. He’s Jack Kelly, not James Garner. And although even the sponsor threw a fit when Warners announced Jack Kelly would be the other star of Maverick, Kelly apparently was able to ride it out, and he and James Garner were able to work together amiably. Again, according to Ed Robertson’s book, the ratings did not rise or fall drastically with whichever Maverick brother was on TV that week.

Gun-Shy takes Maverick firmly into parody territory, having fun, sometimes successfully with the long-running Gunsmoke. And as an aside, the restoration and availability of these old shows not only preserves performances and filming, but allows one to experience writers whose body of work is strong and admirable. The half-hour Gunsmoke episodes are often written by John Meston. Those early Gunsmoke scripts detail in those first seasons that living in the West in the late 1800s was hard. It was hard on men. It was hard on women. In seeing these for the first time, I was often amazed at Meston’s strong sensibilities, and the tough themes he chose, including incest. How the hell did he ever get away with that?

I include that passage here, because his writing is so consistent, so evocative, that I find he is the realm of television writers like Stirling Silliphant, Howard Rodman, Harry Julian Fink and Rod Serling.

But don’t slaughter me yet, I’m back to Maverick and Gun-Shy. It is one of the first filmed series to directly parody other series. Variety shows and comedians like Jack Benny may have done parodies, and funny skits, but one Western didn’t directly take aim at another show, and poke good-naturedly at it. I don’t feel the Marshall Dillon character is on target enough, but the performer who plays the Chester role (Walter Edminston) is right on the money. Again, Maverick, in this set, is testing where it can go and what kind of stories it can tell.

Clint Eastwood appears in “Duel At Sundown,” and continually mispronounces Maverick’s name. I always find it fun to watch Clint before he becomes the iconic Clint.

It’s like seeing Buster Keaton smile at Fatty Arbuckle in “Fatty Goes to Coney Island”.

And just to name one last Maverick episode, “The Saga of Waco Williams,” Maverick meets up with the quintessential Western hero (Wayde Preston), always doing the right thing, knowing how to do it quickly and efficiently, butting into other people’s business and risking his life with no thought of reward. All of which appalls Bret.

Yet, in the last shot, Bret breaks the fourth wall, looks directly into the camera, puzzled and perturbed, “Could I be wrong?”

Along with Stoney Burke and the two volume, last season of Have Gun, Will Travel (don’t get me started!) these four are the most important classic TV releases so far this year.

And I don’t have any aces up my sleeve.